June 2020

from the desk of…

David Regan

Technical Director, NEYT

Greetings from the heart of Scenic Design-- the Scene Shop. Well, actually, due to circumstances beyond our control, I’m writing to you from a desk in my basement. Humble, I know. But hey, a lot of pretty cool things have been created in my basement…well, not this one specifically. Arrival here was pretty recent. So, let’s just say, basements I’ve known throughout my life were always the heart of operations.

Though I trained as a puppeteer, the main focus of my work these days is the design and construction of the scenic worlds of plays. In that realm, occasionally, I also get to muck around in my original place of crafting contentment—the fabrication of props. That’s where I get to practice the creative act that has brought me joy since childhood: taking things and turning them into other things. Cannibalizing furniture, pilfering household items, and mashing them together with all manner of bits of this and that. Poring through thrift shops and flea markets, hoping to spy just the right piece of something. Wandering store aisles (especially hardware and all-for-a-dollar places) with a challenge in mind—the “what”—while letting the shelved abundance spark the answers to “the how.” Because, in the world of prop fabrication, sometimes you aren’t sure exactly what you need until you see it there in front of you.

Then there are props that you don’t have to shop for because what you need to build them is right here. Like cardboard, for instance. I’ve seen entire shows built out of cardboard--scenery, props, even costumes, masks, and puppets. Flat things, dimensional things--it’s all possible with just cardboard, something to draw with (pen, pencil, sharpie, paint,) something to cut with (utility knife or an x-acto; scissors not-so-great in this case) and something to stick it together with (hot glue gun or masking tape.) This is the tale of one such assemblage…

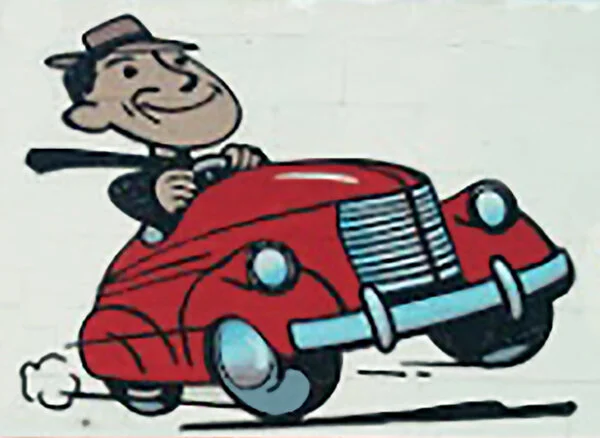

Among the many things I love about NEYT is the fact that it was founded by two clowns. As such, the art of clowning has always had a solid place at the table here and each year, one of the productions is clown-centric. This past November, I had my first experience designing and building one of those shows: Clown T.V. I mention this because that experience confirmed something I had long suspected-- creating clown props is, on the whole, significantly more entertaining than creating their non-clown counterparts. I suppose that it has to do with the Clown World overlapping the Cartoon World (where I have often felt that, in a just universe, we really ought to be living.) In the Clown World, things do not have to appear realistic. In fact, “realistic” could almost be considered “against the rules.” It’s all about exaggeration, caricature, and things that are either far larger or far smaller (whichever is more comical) than they would be in real life.

Sooo, the script for one of the segments in Clown T.V. demanded a car, and, a short while later in the scene, a rocket ship. And each of them had to be large enough to accommodate a family of four. This was also an incredibly fast-paced production, so everything in it, including the actors, had to be able to move on- and off-stage in an instant.

Well, there we have some parameters* to guide the design of these props:

1) They have to be pretty big

2) They have to allow for actor visibility

3) They must be able to move swiftly

4) The need for “home bases.” I haven’t mentioned this one-- with big props you always have to consider where they live when they aren’t on the stage.

* A side note about parameters-- they are Really Good Things. As a designer, I am always grateful for them. You can always let your imagination take flight in a design process. But, just as an airplane--or, for a more pertinent reference, a rocket ship--must have a launch area, your imagination needs a starting point. While we might desire creative freedom, the worst possible scenario for me is one that begins, “Design whatever you feel like,” somewhat akin to being dropped in the middle of the ocean and told I am free to swim any direction I want. Floundering easily ensues.

Anyway, since Realism was uncalled-for, the obvious style choice was Cartoonism. The easiest method of construction for cartoon elements follows cartoon sensibilities--that is, make it all two-dimensional. Which leads us back around to the much-loved, aforementioned cardboard.

The Plan, as it now stood: A 2-D, cardboard cartoon, mounted on a small dolly that has enough structure to support the cardboard, spots for seating, and casters so that it can roll quickly.

The Hitch(es): There are TWO “vehicles” needed, remember? That means more cardboard, more time, and TWO big items for which we need to find off-stage homes.

The First Solution?: Perhaps we can use one cart for both of them and devise some way to attach/detach them VERY quickly from the dolly. That’d work, but it will slow down the transitions. And it’s still a lot of material and labor for a relatively quick gag. Another solution, perhaps?

Let’s think further about form and transition and any similarities between the two vehicles (and here’s where the process gets truly gleeful.) How about something like, oh, I don’t know…a Transformer?

Hah! We could make the car transform into a space ship!

Advantages: Besides saving on material and the logistics of switching them on the cart, this solution will absolutely be:

1) More interesting/challenging/fun to design and build.

2) More inspiring and entertaining for the actors.**

3) Quicker, as the cart won’t have to be taken on and off the stage for the switch.

4) Really cool.

5) FAR more entertaining for the audience (who will now be watching the transformation) than an off-stage switch-out would be.

Leading inevitably, joyously to The ClownCar-RocketShip Conversionmobile.

**A brief side note here about Actors and Props. They have had, throughout the history of theater, a very tempestuous relationship. Actors, their focus necessarily on what they are doing, often neglect to focus enough on what they are doing it with. Many is the poor prop that’s gotten broken or gone missing as a result. Countless other props languish on offstage prop tables, their actors having forgotten to grab them before entering the scene onstage. It’s remarkable how often this is repeated, despite the consternation suffered by the actor upon discovering that they do not have the letter, the watch, the pistol, the whatever, that they are expected to produce momentarily in the scene. Despite all that, reputable props builders will always put the utmost effort into the selection and/or fabrication of the props they provide to the actors. I am convinced that if you give actors props that show an investment of thought, time, and imagination, it can elevate their performance. We, as designers and builders, are creating a world that the actors must inhabit. The more convincingly “real” we can make every aspect of that world--even if it’s a cartoon--the stronger the actors’ belief in their surroundings. That cannot help but have a positive impact on performance. Giving them a “really cool prop”*** can excite and inspire. And if they sense that we have invested in our work, perhaps it will boost their own investment.

***A brief side warning about “Really Cool Props.” While they might seem very amusing and clever, use caution when selecting that path. “Because it’ll be cool” is never an adequate justification for a given design choice. Cool, clever, awesome-- they are all very tempting. But they have to grow out of the substance of your choices; they cannot provide the substance.

But back to the car, Dave!

Fortunately, I had a lot of cardboard around the shop, including some super-thick stuff I had picked up at a graphics outlet and been holding onto for years, waiting for Just The Right Project. For inspiration, I turned to the line styles of the 1950’s and early-1960’s, my favorite era of cartoon design. The car was big and bulbous, with tall roof and large windshield opening. The plan was to have seats for driver and passenger on the dolly, with the other two actors simulating the back seat by standing behind the rest and leaning out to the sides.

The original plan envisioned a car tire and a spaceship fin as two ends of a single piece that could spin around for the change. I spent an awful lot of time trying to make that work. Unfortunately, when the tires were in position, the tips of the fins kept poking up above the fenders and no amount of adjustment could cure the problem. Eventually, I hit that undefinable point where the amount of time spent overbalances the value of the idea. An alternative was needed. As usual, the best plan was the simplest: the fins stayed in place all the time, with the tires as overlays, held in place with magnets. The bottom of the rocket ship was a shape that, when hinged up, could viably be part of the car’s bumper/grill portion. Magnets also kept that piece up in place when the car was in use. The rocket cone top had a block adhered to the back so that when it was simply set on the top of the car, the cone and the block sandwiched the carboard car-top. The entire transition was done in full view of the audience, by cast and crew members, earning them several bursts of applause. Why? Because it was fast, it was silly, and, most importantly, it was unexpected, a sure-fire recipe for audience delight.

Aaannnd, Lift-off!